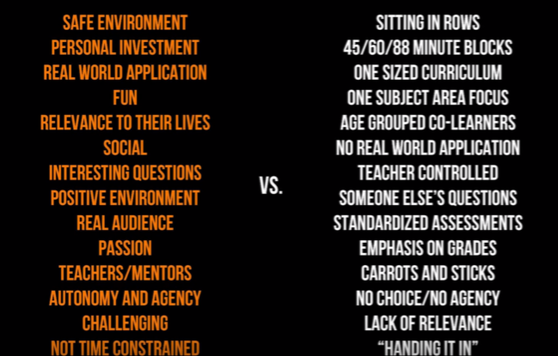

Will Richardson starts off his essay by first offering an allegory. This allegory shows how when left to their own devices, students will find the answers they need and many times in the most innovative ways that we as educators might not have even thought of. After this brief allegorical example, he moves into the real issue. What is real learning and are the educational institutions today doing what helps kids learn or simply repeating a pattern? Richardson writes, "Our story about education has gone basically unrevised for 150 years." (Richardson, 53) Is this really an approach we need to take? When talking about school reform he brings up most of the things we often hear on news reports and with politicians: it focuses on "how to get our students performing 'better' on the tests..." (Richardson, 74). This is all what he calls "Old School" thinking on reform, and it what we have been doing to "reform" the system over the last 150 years. Bigger tests, more to learn, more memorization, and making sure that our students know things that they will forget soon after passing the test. I actually once had a teacher who told us, "You just need to know this for the test. After the test you can just forget about it." But is that all? Are we doomed to repeat the same "reforms" over and over for an eternity? As a History buff, one thing that always comes to mind about why we learn about history is that if we don't learn from it, we will be doomed to repeat it. But Richardson throws another approach out there: the "New School" way. Now, in addressing this approach of reform, he is not in any way trying to castigate the "Old School" model; nor is he saying that the "New School" doesn't have its own limitations. What he is saying is that the "Old School" way of thinking had a very particular reason for why it did things in the way that it did: Scarcity. When the educational models were originally tooled, information was much more scarce. Yes, there were books and teachers who had experience and learned what they were taught and then carried on this tradition of learning and teaching to the next generation. But today, we have an abundance of information. Simply typing, "American Revolution" in Google gives me 22.1 million results (in 0.63 seconds, too). And typing "cheese" gives me 345 million. There is an abundance of information accessible to us at our fingertips today. If I wanted to know an empirical fact, I need only search for it. So why are we still teaching kids facts? When discussing the "New School" approach, he points out that there are six unlearning/relearning ideas that we can take as educators to have a real reform in schools and make the schools ready to meet the challenges posed by the ever-evolving and ever-abundant 21st Century world. They are:

As an educator, the one I would be most committed to concentrating on most would first be "Discover, don't deliver, the curriculum." I think this tackles the biggest issue of not teaching the students empirical facts that they will soon forget, but rather getting the students excited about learning and eventually being fueled themselves with the passion to find the answers along with me (the teacher). It is more about a journey and finding out more about the subject by experiencing it together rather than just saying, "Here's a study sheet, study this, take two pills and call me in the morning." It is getting down in the nitty-gritty with the kids and experiencing and learning ourselves, and from each other in the process. Richardson points out that when he was visiting High Tech High in San Diego, the founder, Larry Rosenstock had said, "We have to stop delivering the curriculum to kids. We have to start discovering it with them." (Richardson, 412) Richardson then paraphrases saying that the "New School" approach moves "away from telling kids what to learn, and when and how to learn it." (Richardson, 412) But rather we need to instill a passion in them to find answers to things by letting them learn about what they want to learn about. So that is definitely a model I want to commit to. For these six, the one that might be the greatest struggle for me would probably be "Do real work for real audiences." Although we could put together digital portfolios or YouTube videos, I think it might be a little bit of a struggle to get the kids excited about it. However, this is linked with "Transfer the Power" so after giving them a little more control over what they want to learn and how they want to go about doing it, it might make the "Do real work for real audiences" less of a struggle. Richardson. W. (2012). Why School?: How Education Must Change When Learning and Education Are Everywhere. Kindle Edition.

2 Comments

9/7/2016 02:45:19 pm

Hello Richard. I appreciated your reflection. I too have had teachers tell me that I only need to know material for an exam and then I could forget about it. If it was worth learning, then I would want to know it past the exam, and if not, then maybe it shouldn't be on the exam in the first place! I think 150 years of no major revisions in education is too long. Our world is a different place than what it was back then. We may essentially want to teach some similar things, but our method of doing so needs to change to meet the needs of today's students and the instant gratifying world we live in. Like you, I would like to prevent history from repeating itself in regards to education.

Reply

Elizabeth Mauerman

9/9/2016 06:56:16 pm

One of my first reactions to Richardson's ideas about getting kids to be invested in a project was wondering how to facilitate the kids in getting passionate about something. I think that there will be some trial and error -- our job is to try new things and discover what works for students and what doesn't. I also thought about the idea that many high school teachers love the content area they are teaching, whereas elementary school teachers often love to work with kids. It's not that single subject teachers don't love kids, it's just that we often want to pass our love of whatever content area to at least some of our students. I think loving what we teach is a great start to getting the students interested and passionate about something -- it shows them that it is possible. They just have to find what makes them tick.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRichard Sable is from Vista, CA and graduated from Azusa Pacific University in 2014 with a B.A. in Social Science and is currently working on his single subject teaching credential in the field of Social Science at CSU, San Marcos. Archives

March 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed